Parasites are often thought of as passive hitchhikers, quietly living off the resources of their host.

However, in the wild, some parasites go far beyond simply feeding. They hijack minds, manipulate behaviours, and turn their hosts into walking, swimming, or crawling vehicles for their own survival and reproduction. These manipulations can be so specific, so targeted, that it’s hard not to see them as something out of science fiction. Here are some of the most chilling examples of parasites that control their hosts with terrifying precision.

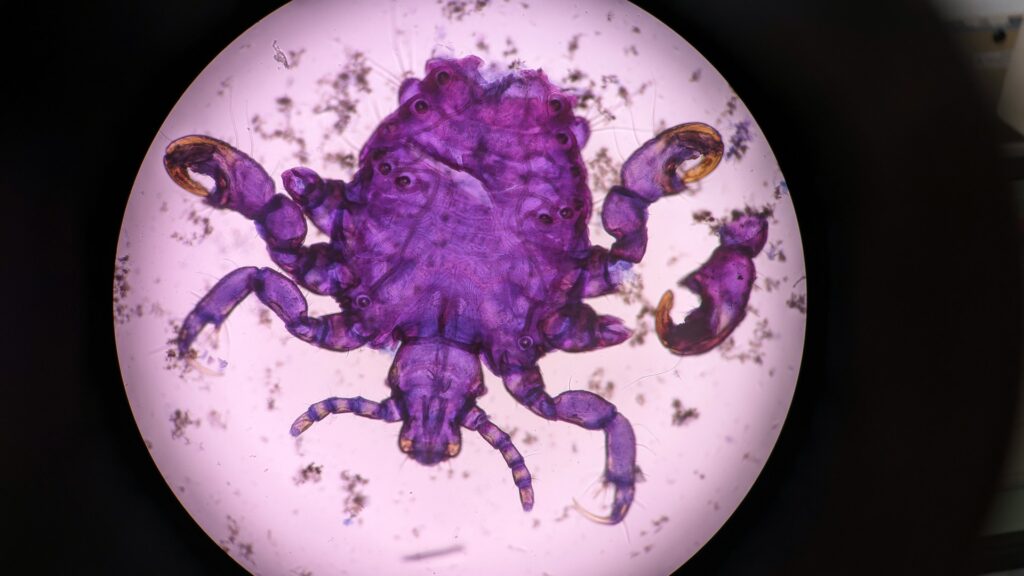

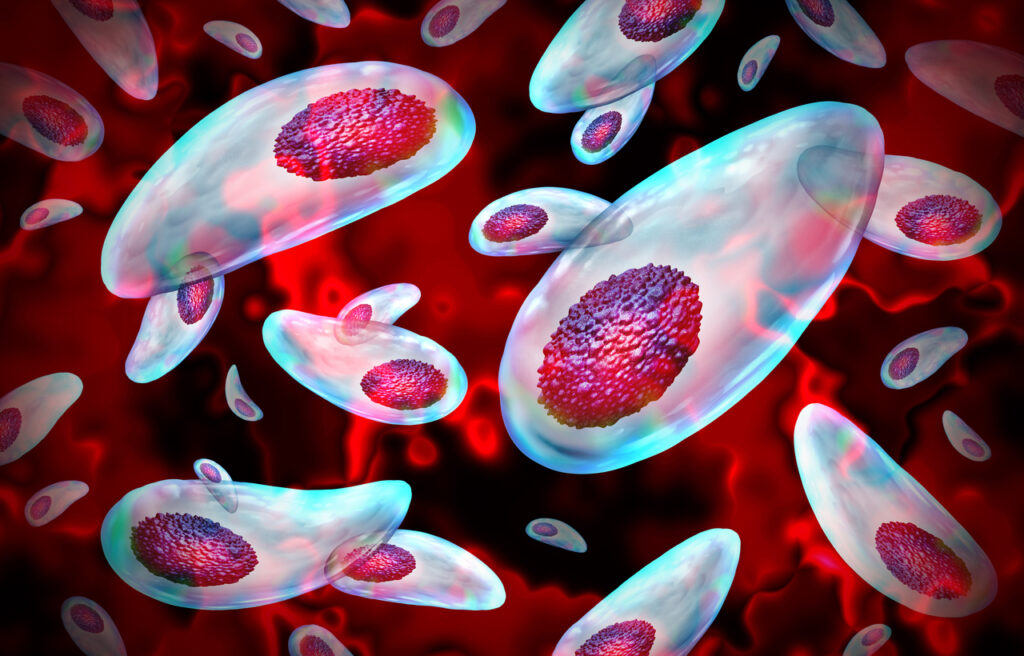

Toxoplasma gondii

This microscopic parasite infects warm-blooded animals, including humans, but it can only reproduce in cats. To complete its life cycle, it has a disturbing trick: when rodents like rats or mice become infected, they lose their natural fear of cat scent. In fact, some studies suggest they become attracted to it.

This behavioural shift increases the chance the rodent will be eaten by a cat—delivering the parasite to its ideal host. Toxoplasma can also infect humans, and while it doesn’t turn people into cat-loving zombies, some research links it to changes in risk-taking behaviour, and even personality changes. The extent of its influence on human psychology is still being explored.

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (zombie-ant fungus)

Perhaps the most infamous example, this parasitic fungus infects carpenter ants in tropical forests. Once inside, it takes over the ant’s central nervous system, forcing it to climb vegetation and clamp its mandibles onto a leaf or twig.

The fungus then kills the ant and sprouts a stalk from the back of its head, releasing spores that fall onto the forest floor to infect more ants. The level of behavioural control is astonishingly precise—even the time of day and height of the final perch appear to be dictated by the fungus for maximum spore dispersal.

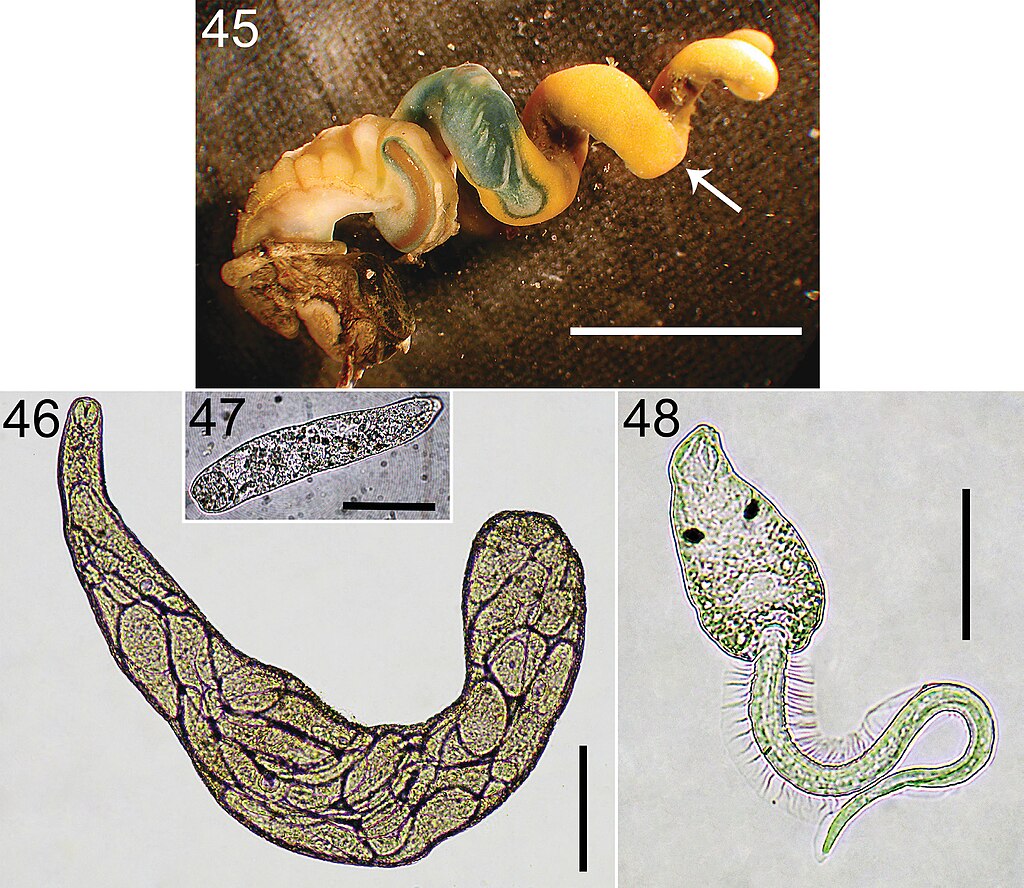

Leucochloridium paradoxum (green-banded broodsac)

This parasitic flatworm targets birds, but it starts its life inside a snail. Once inside, it invades the snail’s eye stalks, causing them to swell and pulsate with green and yellow stripes. The parasite then takes control of the snail’s behaviour, pushing it to move into open, exposed areas during daylight.

The grotesque appearance and movement of the eye stalks make them look like juicy caterpillars, attracting birds. When a bird bites, the parasite gets inside and continues its life cycle. It’s a vivid, disturbing example of a parasite manipulating both appearance and behaviour with eerie accuracy.

Dicrocoelium dendriticum (lancet liver fluke)

This parasite uses ants as an intermediate host, but its final target is the liver of grazing mammals like cows or deer. After being eaten by a snail and excreted in its slime, the fluke is ingested by ants.

Inside the ant, it sends one of its larvae to the brain, where it takes control. Every evening, the infected ant climbs to the top of a blade of grass and clamps down, increasing the chance it will be eaten by a passing grazer. If it doesn’t get eaten, the ant goes back to its normal routine until night falls again, repeating the cycle. It’s a chilling example of on-demand behavioural control.

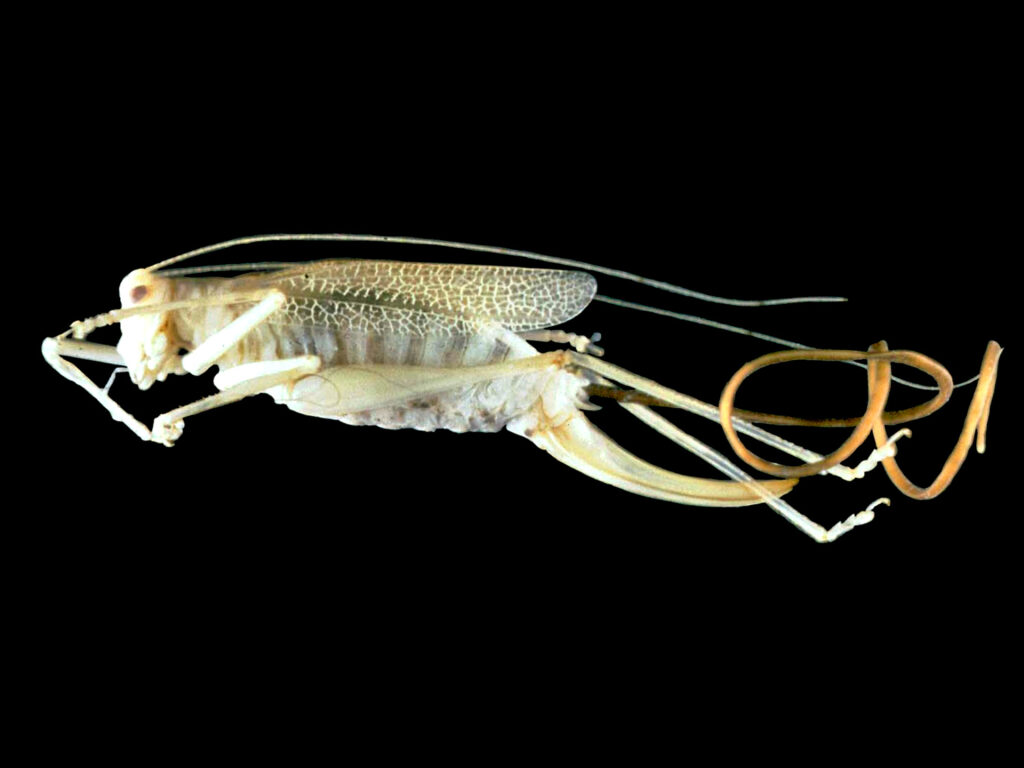

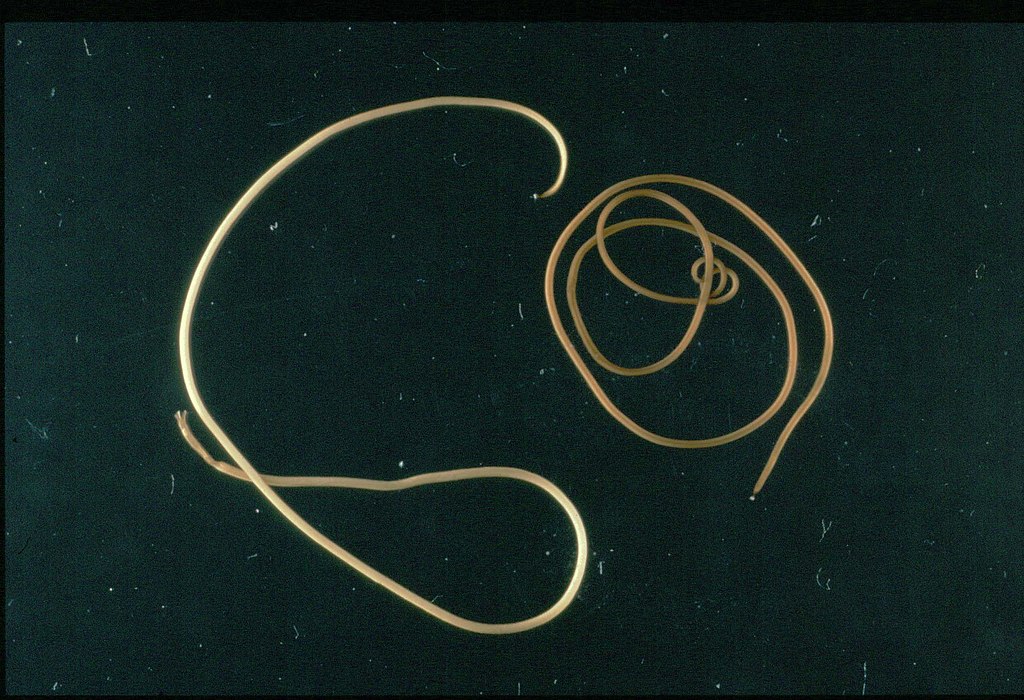

Spinochordodes tellinii (hairworm)

This parasite infects grasshoppers and crickets, but it needs water to reproduce. After developing inside the insect, it triggers suicidal behaviour: the host is compelled to jump into water. Once submerged, the worm exits the body, sometimes several times longer than the insect itself, and begins its aquatic reproductive phase.

The host often drowns or is left severely debilitated. Scientists believe the worm manipulates proteins in the host’s brain to influence its behaviour. It’s a terrifying example of a parasite using its host like a disposable vehicle.

Glyptapanteles wasps

This parasitic wasp lays its eggs inside caterpillars. When the larvae hatch, they feed on the caterpillar’s internal organs but avoid killing it—at least at first. Once fully developed, they chew their way out and form cocoons nearby.

But the story doesn’t end there. The caterpillar, though mortally wounded, starts behaving protectively—standing over the cocoons, thrashing violently at predators, and guarding the developing wasps. It eventually dies, but not before giving the parasites their best shot at survival. How the wasp larvae control this post-exit behaviour is still not fully understood.

Sacculina carcini

This barnacle parasite targets crabs, but it doesn’t latch on from the outside. Instead, it injects cells into the crab that grow into a root-like system throughout the host’s body, essentially taking it over from the inside.

The crab stops growing, stops moulting, and becomes infertile. Males even develop female characteristics. The parasite hijacks the crab’s reproductive system to care for its own eggs, which the crab protects and aerates as if they were its own. It’s not just body control—it’s identity theft.

Euhaplorchis californiensis

This parasite lives in the brain of the California killifish, but it starts its life in snails and completes it in birds. To get there, it manipulates the fish’s behaviour, making it swim erratically and spend more time near the surface, flashing its belly.

This makes the fish easier for birds to spot and catch. Once inside a bird, the parasite reproduces and its eggs are deposited into the water via droppings, starting the cycle again. Researchers have found that infected killifish are up to 30 times more likely to be eaten.

Paragordius tricuspidatus

This hairworm species is similar to Spinochordodes tellinii, also inducing suicidal water-seeking behaviour in its host (typically crickets). But what makes it more unsettling is its ability to time the manipulation. It doesn’t act immediately but waits until the worm is ready to emerge.

When the moment arrives, the cricket jumps into the water, and the worm exits, leaving the host to drown. The manipulation is so targeted that it occurs only when it benefits the parasite.

Myrmeconema neotropicum

This parasite infects tropical ants, and it has a particularly bizarre strategy. Once inside, it changes the appearance of the ant’s abdomen from black to bright red and makes it swell, mimicking a berry. The ant also starts holding its rear end up in the air.

Birds mistake the ants for fruit, eat them, and the parasite completes its life cycle in the bird’s gut. It’s a mix of behavioural and morphological manipulation designed to fool one species and sacrifice another.

Parasites are often hidden, often overlooked.

However, as these examples show, some of them are master manipulators capable of orchestrating life-and-death decisions inside their hosts. These tiny organisms can change the course of behaviour, alter appearances, and override survival instincts—all to further their own survival.

What makes it all the more unsettling is how precise and efficient these strategies are. They offer a chilling glimpse into the complexity of nature’s darker strategies, and remind us that control in the animal kingdom doesn’t always belong to the biggest or the strongest. Sometimes, it’s the smallest creatures that pull the strings.