It sounds like science fiction, but the idea of bringing extinct animals back to life is inching closer to reality.

With breakthroughs in cloning, gene editing, and ancient DNA recovery, scientists are now revisiting the past (literally!) and trying to reverse some of the damage we’ve done. While there are still huge ethical and ecological questions, the idea of “de-extinction” isn’t just a theory anymore. It’s an active field, and some species are already being worked on in labs today.

Here are a few of the extinct animals that scientists are genuinely trying to bring back, and how close we are to seeing them again.

The woolly mammoth might walk the tundra again.

No animal symbolises de-extinction quite like the woolly mammoth. These Ice Age giants disappeared around 4,000 years ago, but frozen carcasses have preserved their DNA surprisingly well. Scientists, most notably at a company called Colossal Biosciences, are now attempting to use gene editing to create a hybrid between an Asian elephant and a woolly mammoth.

The goal isn’t just to play Jurassic Park. Researchers hope that reintroducing mammoth-like elephants to the Arctic tundra could help restore degraded ecosystems. While we’re still years away from a living, breathing mammoth, prototypes using elephant cells edited with mammoth traits are already in development.

The passenger pigeon could fill forests again.

Once numbering in the billions across North America, the passenger pigeon was hunted to extinction by the early 20th century. But because it died out relatively recently, its DNA is still in good shape, and scientists are working to recreate the species by editing the genome of the closely related band-tailed pigeon.

The group Revive & Restore is leading the charge, aiming to reintroduce genetically engineered birds that behave like passenger pigeons. Early genetic work is underway, and while there’s no living specimen yet, the progress on sequencing and editing is promising.

The thylacine may be closer than we thought.

Also known as the Tasmanian tiger, the thylacine was a striped, dog-sized marsupial native to Australia and Tasmania. It was officially declared extinct in the 1930s, but recent advances have brought it back into scientific conversation.

Researchers at the University of Melbourne, now collaborating with Colossal, are using CRISPR technology and the genome of a close relative, the numbat, to try to recreate a thylacine-like animal. Tissue culture work and embryo development are in the pipeline, and the team hopes to have something viable within the next decade.

The Pyrenean ibex was already cloned, albeit briefly.

The Pyrenean ibex, or bucardo, went extinct in 2000 when the last known female was crushed by a fallen tree. But scientists had preserved her DNA. In 2003, they used it to create a cloned ibex via surrogate goat—the first extinct animal to be revived, if only temporarily. The clone died of lung failure minutes after birth, but it proved the concept.

Since then, the cloning technique has improved, and more attempts are being considered using related mountain goat species as surrogates. Of all de-extinction efforts, this one has already crossed a major milestone, if only briefly.

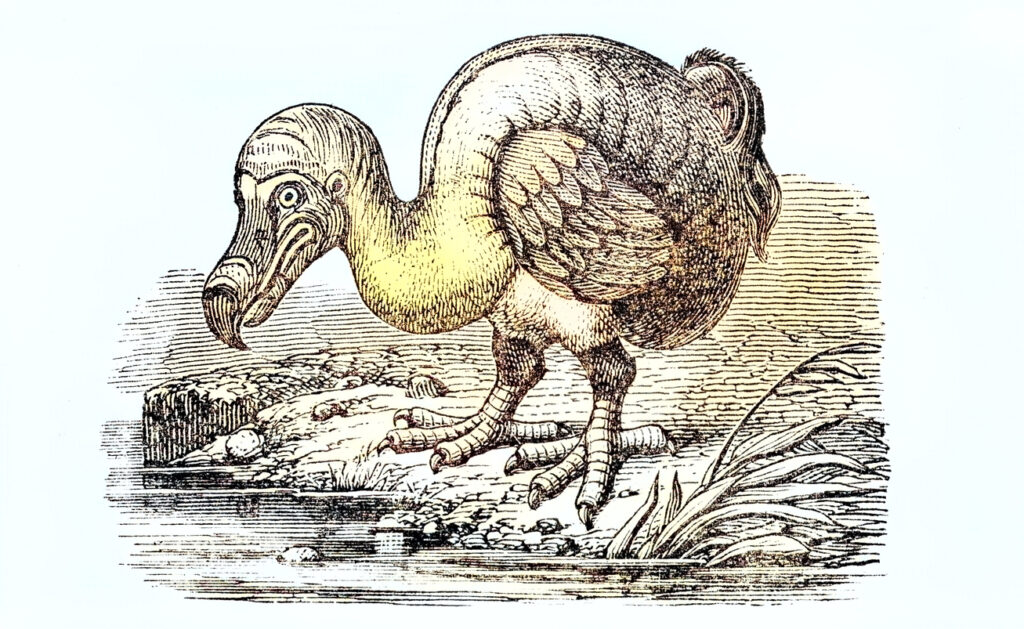

The dodo may not be gone for good.

The dodo, a flightless bird native to Mauritius, has become shorthand for extinction itself. Wiped out by invasive species and human hunting by the late 1600s, it left no living relatives. But its closest genetic match is the Nicobar pigeon, and DNA from dodo remains has now been successfully sequenced.

Colossal Biosciences is working on a long-term plan to edit Nicobar pigeon DNA to recreate dodo traits, potentially reintroducing a dodo-like bird to managed reserves. It’s a complex undertaking, but the DNA work has already started.

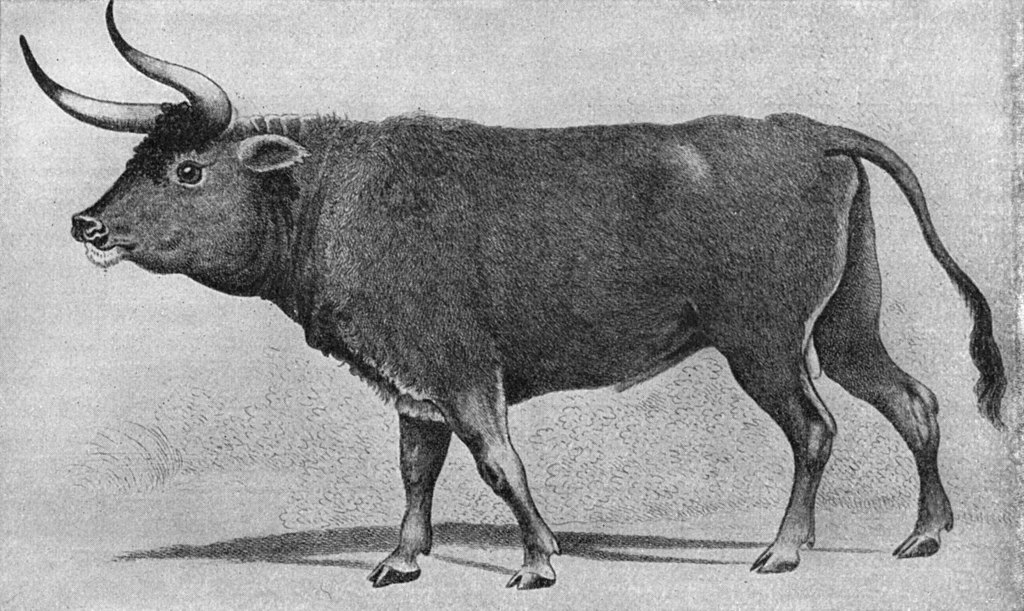

The aurochs could return through selective breeding.

The aurochs was a massive wild ancestor of domestic cattle, roaming Europe until it went extinct in the 1600s. Because cattle descended directly from aurochs, scientists have tried to recreate the original animal through selective breeding, choosing cattle breeds that still retain some aurochs-like traits.

The Tauros Programme and other efforts in Europe are working to breed a modern animal that’s visually and ecologically similar to the aurochs. It’s not cloning or gene editing, but it’s a form of de-extinction based on restoring ancient genetics.

The gastric-brooding frog might hop again.

This strange little frog from Australia had a unique trait—females swallowed their fertilised eggs, shut down their stomach acid, and gave birth through their mouths. It went extinct in the 1980s, but in 2013, scientists succeeded in cloning its DNA into a closely related frog species using somatic-cell nuclear transfer.

Although the embryos didn’t survive long, the experiment showed that partially reviving extinct amphibians was feasible. Work is ongoing to refine the technique and eventually bring the frog back entirely.

The quagga could reappear through back-breeding.

The quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra with distinct striping, mostly on the head and neck, and a more horse-like appearance. It went extinct in the 1880s, but modern zebras still carry some of its genes.

The Quagga Project in South Africa has been selectively breeding zebras that resemble the quagga, with remarkable results. The animals produced aren’t genetically identical, but they are functionally and visually close. It’s a long-term project, but the quagga is already partially restored in form.

The Steller’s sea cow could help kelp forests recover.

This enormous, slow-moving marine mammal was hunted to extinction in the 18th century, just 27 years after it was first described. It was closely related to the dugong and manatee, and there are growing calls to revive it, especially given the ecological role it played in maintaining kelp forests.

While no de-extinction programme is actively cloning Steller’s sea cows just yet, recent genome sequencing has provided a full genetic map. If manatees or dugongs could serve as surrogates, this is one species that might eventually make a comeback.

The great auk may be a future project in waiting.

A flightless bird that once thrived in the North Atlantic, the great auk was hunted for meat and feathers until it vanished in the mid-1800s. Like the dodo, it had no living descendants, but plenty of preserved museum specimens exist, many of which have usable DNA.

Revive & Restore and other organisations have considered the great auk a candidate for de-extinction. Using razorbills, its closest living relatives, as surrogates, they hope to edit embryos with auk genes and restore breeding colonies in protected areas. While not underway yet, the groundwork is being laid.

The Carolina parakeet could return to American skies.

This brightly coloured parrot was once common across the eastern United States, but habitat loss and hunting drove it extinct by the early 20th century. As one of the few parrots native to North America, its disappearance left a big gap in ecosystems.

With preserved specimens in museums and modern genetic techniques, scientists believe the Carolina parakeet could be brought back using the DNA of close relatives like the sun parakeet. The main hurdles will be recreating its ecological niche, and ensuring its reintroduction doesn’t conflict with modern land use.

The idea of bringing back extinct species is no longer just a fantasy—it’s a real scientific pursuit.

Whether it’s through cloning, CRISPR, or selective breeding, the tools now exist to start undoing what human activity has erased. But it’s not as simple as just making an animal and releasing it into the wild. These creatures need habitats, ecological roles, and protection from the same pressures that wiped them out in the first place.

Still, there’s something hopeful about the idea. It shows we’re not just passive witnesses to loss. In fact, we’re capable of making amends, at least in some cases. And with each new breakthrough, the line between past and present grows a little blurrier.