When people think about conservation, they often picture protected forests, wildlife reserves, or hands-on rescue work.

But behind the scenes, one of the most powerful forces shaping modern conservation efforts is technology. It’s not just a tool for scientists—it’s become a vital part of how we understand, monitor, and protect the natural world. Technology allows us to work faster, scale up efforts, reduce guesswork, and make more informed decisions. It bridges gaps between research, action, and policy, especially in areas where traditional conservation methods fall short.

From tracking endangered animals to restoring coral reefs, technology is playing a growing role in helping us fight back against biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, and climate change. And while it’s not a silver bullet, it’s giving conservationists more data, better tools, and faster ways to respond. When applied thoughtfully and ethically, it brings real hope to efforts that were once considered too slow or resource-intensive to scale.

Tracking and monitoring wildlife

One of the most visible ways technology is helping is through tracking and monitoring. GPS collars, drones, and satellite tags allow scientists to follow animal movements in real time. This helps us understand migration patterns, identify critical habitats, and detect threats like poaching or habitat encroachment. For example, elephant collars can show when a herd is entering farmland, allowing local rangers to intervene before conflict happens. Similarly, satellite tracking of sea turtles helps researchers locate nesting beaches and understand how ocean currents affect their journeys. This kind of real-time insight has transformed how we think about wildlife corridors and transboundary protection efforts.

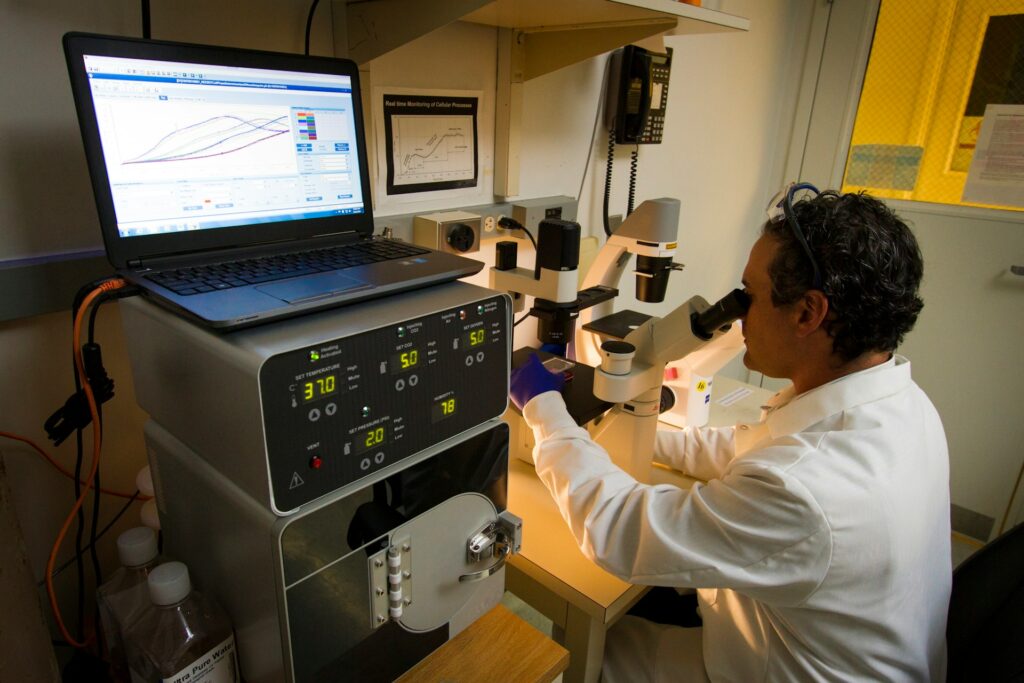

Camera traps are another game-changer. These motion-sensitive cameras are placed in forests, deserts, and wetlands to capture images of elusive species without disturbing them. They’ve helped confirm the presence of animals in areas where they were thought to be extinct, like the rediscovery of the black leopard in Kenya. Artificial intelligence is now being used to automatically analyse millions of images, identifying species and behaviours far faster than humans could manage on their own. According to a 2022 study in Nature Communications, automated image recognition systems have increased species identification accuracy while drastically reducing the time spent sorting through data (source). These systems are also being integrated into community-led conservation work, making it easier for local groups to track wildlife with minimal training.

Reaching remote areas and fragile ecosystems

Drones have revolutionised how we see remote or dangerous areas. They’re used to survey forests, count nesting birds on cliffs, and even map coral reefs. Unlike manned aircraft, drones are cheaper, safer, and less disruptive to wildlife. In places like the Amazon, they’re helping conservation groups detect illegal logging, giving authorities a chance to act before too much damage is done. Thermal imaging and high-resolution cameras attached to drones provide vital data that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to obtain on foot.

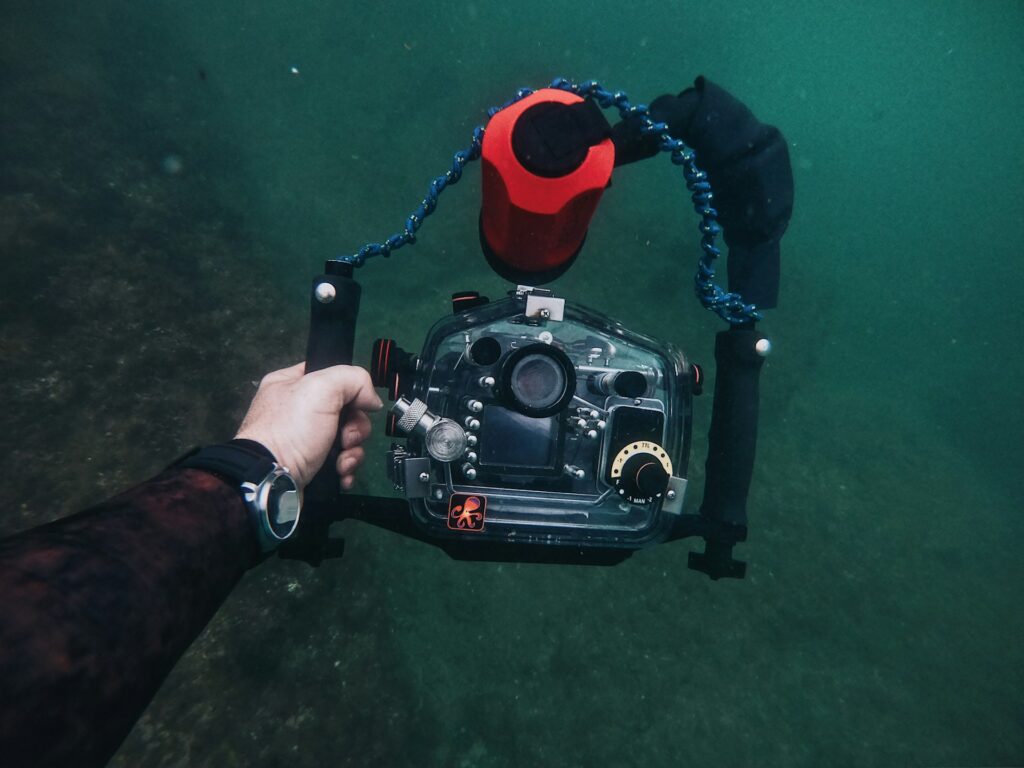

Underwater, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) explore deep-sea environments previously out of reach. These robotic systems are used to monitor coral health, document biodiversity on the seafloor, and even collect samples from volcanic vents. In Australia, robotic subs have helped monitor the Great Barrier Reef’s bleaching events and assess damage in real time. Elsewhere, long-term underwater monitoring stations are collecting temperature, salinity, and current data to support large-scale ecosystem models.

Listening to nature

Then there’s acoustic monitoring. Underwater microphones and forest-based audio sensors can pick up sounds from species that are hard to spot, such as whales, frogs, and birds. These recordings help researchers track populations over time, study migration, and even measure the impact of noise pollution on animal behaviour. Technology is helping us listen to the wild in ways we never could before. In some cases, acoustic systems have detected poachers through gunshot recognition or engine noise before any damage was done.

A project by Cornell University, called the Elephant Listening Project, uses hidden microphones to track forest elephants in Central Africa. By analysing their low-frequency rumbles, researchers can study movement patterns and identify poaching risks. This kind of passive monitoring means fewer disturbances and more detailed data over longer periods. It’s particularly valuable in dense forests where visual observation is nearly impossible.

Protecting marine life

Technology is also transforming how we protect marine ecosystems. Robotic underwater vehicles are used to explore and map fragile habitats like deep-sea coral reefs. Satellite imagery can detect illegal fishing boats and monitor water temperatures, helping scientists predict coral bleaching events before they happen. Programmes like Global Fishing Watch use satellite data to track commercial fishing vessels around the world, exposing harmful or illegal practices in near real-time.

Thermal sensors and remote cameras placed on coastlines also help track seal and seabird populations, providing essential data for marine protected area management. In some regions, real-time alerts based on sensor networks have helped authorities respond quickly to marine strandings or oil spills. Combined with mobile apps that allow fishers and local communities to report unusual sightings, these technologies help create a feedback loop between data collection and action.

Supporting habitat restoration

In habitat restoration, tech has an equally important role. In some projects, drones are being used to plant seeds in deforested areas. They can cover far more ground than people on foot and can reach areas that are difficult or dangerous to access. Software modelling tools also help scientists plan reforestation efforts based on local soil, climate, and biodiversity data, making sure the right plants go in the right place.

In Kenya, for example, the company BioCarbon Engineering has used drone-based reforestation techniques to plant tens of thousands of trees in degraded landscapes. Modelling software also allows conservationists to simulate how different planting strategies will affect ecosystem health, providing a data-backed foundation for large-scale restoration. These models can also forecast how restored areas will perform under various climate scenarios, helping to future-proof recovery efforts.

In coastal zones, technologies like automated oyster reef restoration systems and satellite-monitored mangrove planting are making a difference. Restoration teams can now visualise the impact of their efforts and adjust approaches in real time, saving time, money, and resources.

Enhancing collaboration and data sharing

Tech isn’t just for fieldwork either. Data platforms are allowing conservationists to share information more easily across borders. Collaborative apps help scientists pool sightings of endangered species, report threats, and build open-source databases. This kind of global cooperation is essential, especially as many species migrate across regions and continents.

Platforms like GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) allow researchers to share biodiversity data, making it easier to track changes in species populations over time. Open-access tools like SMART (Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool) help park rangers log patrols, incidents, and observations—streamlining anti-poaching work and improving transparency. Cloud-based mapping tools like EarthRanger allow rangers, ecologists, and managers to visualise everything from animal movements to fence breaches and threat hotspots.

Even citizen science has been boosted by tech. Apps like iNaturalist and eBird let the public log wildlife sightings, feeding vast datasets used by researchers and policymakers. In turn, this helps build public engagement and awareness—something that’s often just as vital as the science itself.

The rise of genetics and environmental DNA

Genetics and biotechnology have also opened new frontiers in conservation. DNA barcoding helps identify species from a single hair or droplet of water, while environmental DNA (eDNA) allows scientists to detect animals from traces they leave in soil, air, or water. This means we can monitor rare species without ever seeing them. In some cases, researchers are even using gene editing techniques to help fight invasive species or disease.

A notable example comes from the UK, where conservationists used eDNA to confirm the presence of the great crested newt in ponds where traditional surveys had failed. This approach reduces the time and cost of fieldwork while minimising disturbance to sensitive species. According to the Environment Agency, eDNA has now been adopted in official survey protocols.

CRISPR gene-editing tools are also being trialled in tightly controlled conservation scenarios. Scientists are exploring the possibility of using gene drives to reduce invasive rodent populations on islands that threaten seabird colonies—though this approach remains controversial and raises serious ethical questions.

The limits and risks of relying on tech

Still, technology alone won’t save the planet. Tools are only useful when paired with strong policy, community involvement, and long-term funding. Tech can give us the information, but it’s people who have to act on it. There’s also a risk that over-reliance on gadgets could overshadow more traditional, low-tech approaches that are still highly effective. Some conservationists worry that an obsession with shiny tools could move funding away from fieldwork or essential community outreach.

There are also ethical questions. Who owns the data? How is it used? Can surveillance technology be misused in ways that harm wildlife or local communities? As we move further into a high-tech conservation era, it’s essential to keep asking these questions and include local voices in every part of the process. Equitable access to technology and respect for Indigenous knowledge must be part of the conversation.

Additionally, maintenance and training are ongoing concerns. Devices break, software updates, and power or internet access can be limited in the field. Ensuring that conservation tech doesn’t become obsolete or dependent on one-off funding is key to making it truly sustainable.

Technology is being put to good use

There’s no doubt that technology is helping conservation become smarter, faster, and more precise. It’s letting us see the invisible, reach the unreachable, and act in ways that weren’t possible a decade ago. Used responsibly, it’s one of our best chances to protect the species and ecosystems we still have left.

In the face of climate change and accelerating extinctions, we need every advantage we can get. And while the natural world might not be built on code and circuits, tech is helping give it a fighting chance—if we use it wisely, ethically, and inclusively.