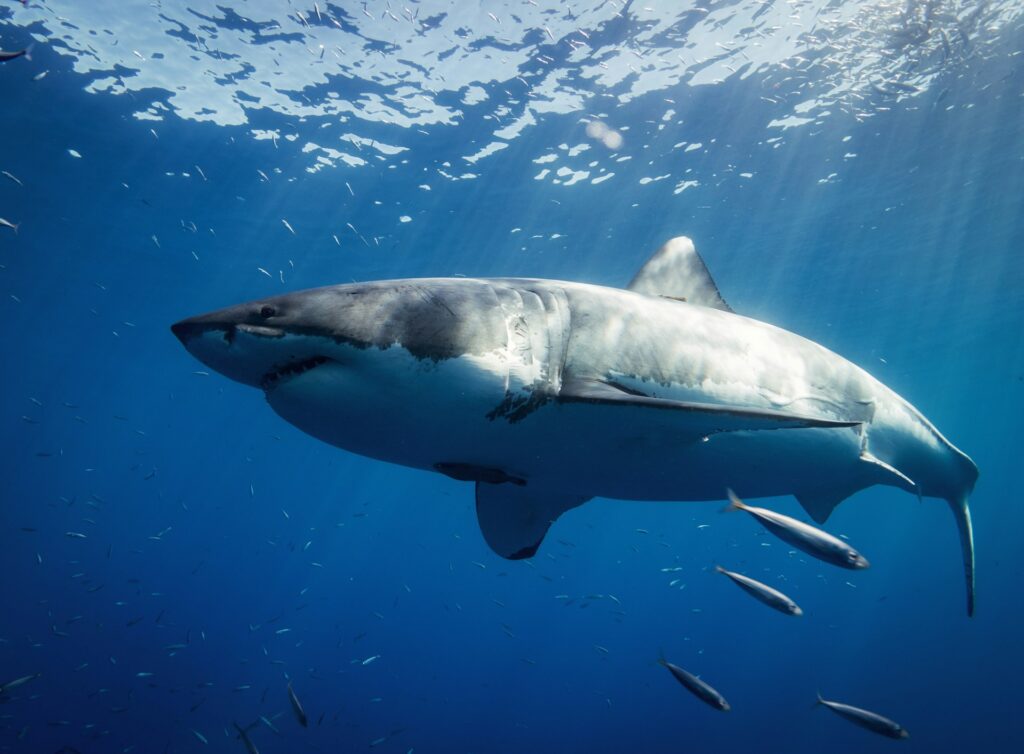

We often picture great white sharks as cold, instinct-driven predators, but science is telling a deeper story.

New research suggests these animals are far more intelligent, curious, and behaviourally complex than we ever imagined. That’s not to say that they can’t be downright deadly, or to suggest that you should hop into the ocean and go for a swim with one, but these incredible creatures certainly deserve more understanding and empathy.

1. They’re far more curious than once believed.

Great whites aren’t the mindless eating machines they’re often made out to be. Researchers tracking sharks off coastlines have found that they often approach unfamiliar objects slowly and circle them multiple times, appearing to assess whether they pose a threat or hold interest. They don’t instantly bite—they observe, test, and even appear to hesitate.

This shows a kind of environmental awareness that’s closer to conscious curiosity than simple instinct. In fact, their tendency to ‘taste’ surfboards or floating objects without consuming them suggests they’re exploring more than attacking. They want to know what something is, not just react to it.

2. They have incredible spatial memory.

Studies using satellite tags have shown that great whites return to the same feeding and birthing areas year after year, even if they’re separated by thousands of miles. These aren’t random migrations—they’re precise, intentional routes that demonstrate strong spatial memory and a deep familiarity with their territory.

This memory allows them to navigate across vast oceans using environmental cues like water temperature, salinity, and even magnetic fields. It’s not just about survival—it’s about planning. They know where they’ve been and where they’re going, and they return with remarkable accuracy.

3. Individual sharks show consistent personalities.

Just like dogs or dolphins, great whites can show personality traits that persist over time. Some are consistently more cautious, while others are bold and exploratory. In long-term studies, researchers have noted specific individuals returning with similar behaviour patterns year after year.

This isn’t just random mood variation. It points toward fixed traits, like introversion or boldness, that influence how each shark engages with its environment. Understanding these traits helps researchers predict how individual sharks may respond to new challenges or human interaction.

4. They show behavioural flexibility in hunting.

Great whites aren’t locked into a single hunting style. In different habitats, they adjust their techniques based on what prey is available. For example, near seal colonies, they strike from below with explosive speed. But in fish-heavy zones, they rely more on chase tactics and tracking movements.

This kind of tactical switching isn’t purely instinctual—it suggests learning. Young sharks often mimic older ones, and techniques appear to evolve over time, especially in regions where prey patterns shift due to climate or human impact. It’s a sign of intelligence built on experience.

5. They avoid humans more often than not.

Despite their fearsome reputation, great white sharks rarely target humans. Most encounters end with the shark swimming away without making contact. In fact, recent tagging studies have shown that sharks frequently detect humans in the water and simply pass by without investigating further.

This behaviour hints at selectivity and caution. Rather than mindless aggression, great whites seem to assess humans as unfamiliar or unsuitable prey—and often decide we’re not worth the risk. This makes “mistaken identity” bites far more plausible than premeditated attacks.

6. Some seem to engage in play.

Footage of young great whites leaping out of the water, playing with kelp, or tossing objects like seaweed or debris around has puzzled researchers. These actions serve no obvious survival function—suggesting the sharks might be engaging in play.

Play behaviour in animals is often linked to cognitive development, learning, and stress relief. If sharks are truly playing, it points toward a level of mental complexity that’s typically only acknowledged in mammals and birds. It’s not just muscle—they’ve got minds that need stimulation.

7. Their brains are larger and more advanced than we thought.

Dissections and brain scans have revealed that great whites have a well-developed cerebellum and large olfactory bulbs. These structures help them process complex sensory information, track prey, and navigate long distances. But they also suggest a greater capacity for learning and memory than expected.

Compared to other fish, their brains are proportionally large, especially in regions associated with emotion and decision-making. That doesn’t mean they feel exactly like humans—but it does mean they’re working with more than just basic instinct. Their brains are built for strategy, not just reaction.

8. They appear to form basic social structures.

While typically solitary, great whites do sometimes gather at feeding grounds or migration hotspots, and researchers have observed informal pecking orders. Larger individuals often eat first while smaller ones hang back and avoid conflict by waiting their turn.

This suggests that sharks aren’t entirely asocial. Their ability to coexist, even temporarily, in shared spaces without constant aggression implies they use non-verbal cues to establish social order. Body posture, proximity, and swimming patterns all play a role in communication, even if it’s subtle.

9. They likely experience a range of emotional states.

While it’s difficult to confirm emotional experiences in animals that don’t vocalise, great whites show clear behavioural shifts under stress, excitement, or fear. Their heart rates increase, their body posture changes, and they sometimes flee when surprised or overwhelmed.

These reactions mirror emotional states seen in other intelligent animals. Whether it’s curiosity, agitation, or caution, great whites demonstrate that they’re emotionally responsive to their surroundings—an important clue that they have internal experiences we’re only beginning to understand.

10. They use decision-making, not blind reaction.

Rather than attacking on sight, great whites tend to circle, observe, and approach with caution. Even when prey is nearby, they don’t always strike immediately. They assess, change course, and sometimes disengage completely.

This points to decision-making driven by experience and context. Whether it’s avoiding a seal decoy, swimming past a diver, or reacting to an unfamiliar boat, sharks are calculating risk versus reward. They’re not creatures of blind habit—they’re strategic thinkers of the sea.