From food packaging to the clothes we wear and even the air we breathe, plastic has become so deeply embedded in our daily lives that it’s hard to imagine a world without it.

And yet, as convenient as synthetic materials may be, their legacy is now coming back to us in a form that’s harder to see but even more alarming: microplastics. These microscopic fragments have become one of the most persistent and widespread pollutants of our time, showing up not only in our oceans and soils but in our bodies, bloodstreams, and lungs.

As more research emerges, we’re discovering that microplastics are far from benign. They’re infiltrating natural systems, disrupting ecosystems, and raising serious questions about human health. What started as a conversation about waste and recycling has become a global concern involving everything from industrial production and agricultural systems to hormone disruption and immune function.

What exactly are microplastics?

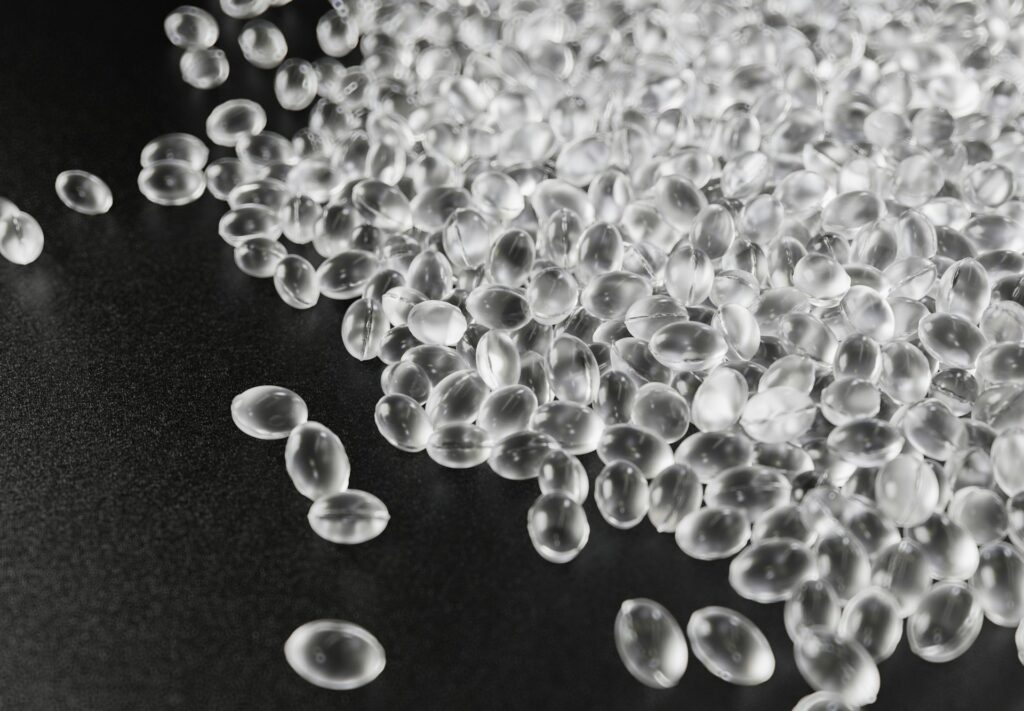

Microplastics are plastic particles less than 5 millimetres in diameter — though many are much smaller, almost dust-like. These fragments come from a wide variety of sources and break down in a range of ways, but their defining trait is that once they’re loose in the environment, they’re practically impossible to remove. And as small as they are, they’re adding up — quickly.

There are two main types:

Primary microplastics are deliberately manufactured to be tiny. These include microbeads once found in facial scrubs and toothpaste, as well as the microfibres released when synthetic clothing is washed. One load of laundry can shed hundreds of thousands of these fibres, especially from items made of polyester or acrylic.

Secondary microplastics are the result of larger plastic products breaking down over time. Packaging, plastic bags, bottles, fishing nets, car tyres, paint flakes — all of these shed smaller pieces through UV exposure, weathering, and mechanical wear.

Unlike organic matter, plastic doesn’t biodegrade. It just breaks into smaller and smaller pieces, persisting in the environment for centuries.

Where are microplastics found?

Put simply: they are everywhere. Researchers have found microplastics in some of the most remote environments on Earth. They’ve been detected in Antarctic snow, deep-sea sediments, high-altitude alpine air, Arctic sea ice, and even within the guts of marine animals that live kilometres below the ocean surface.

A study published in Nature Geoscience found microplastics raining down from the sky in the Pyrenees mountains — suggesting that these particles can travel long distances on wind currents. In the UK, researchers have found microplastics in drinking water, both tap and bottled. In fact, a 2019 WHO report estimated that a litre of bottled water can contain hundreds, even thousands, of microplastic particles.

Marine ecosystems are particularly affected. The IUCN estimates that over 14 million tonnes of plastic enter the ocean each year, and much of that ends up as microplastic. These particles are eaten by plankton, fish, seabirds, and whales, becoming embedded in the food web. It’s estimated that humans now consume around a credit card’s worth of plastic every week — mostly through water, food, and air.

At home, microplastics come from a surprising number of sources: carpets, furniture, cleaning products, and synthetic clothing. Indoor air often has higher concentrations of microplastics than outdoor air due to the constant shedding of fibres from upholstery, rugs, and plastic-based household items.

How do microplastics impact the environment?

In natural systems, microplastics interfere with biological and ecological processes at nearly every level. Marine animals ingest them accidentally, mistaking them for plankton. These particles can accumulate in their digestive tracts, leading to internal injury, reduced feeding, and even death. Microplastics have been found in mussels, crabs, sardines, and sea salt.

Plastics often act as chemical carriers. They can absorb toxins such as pesticides, heavy metals, and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), which hitch a ride into the digestive systems of wildlife. The consequences range from altered hormone function and reproductive issues to developmental abnormalities in offspring. And because predators consume prey, these toxic effects climb the food chain.

On land, microplastics are found in agricultural soils — often introduced through sewage sludge (used as fertiliser), plastic mulching, or the breakdown of plastic containers and irrigation systems. Once in the soil, microplastics can disrupt water retention, harm earthworms and fungi, and alter nutrient cycling. A study published in Science of the Total Environment showed that these changes can reduce crop productivity and long-term soil health.

Atmospheric microplastics are an emerging concern. These airborne particles are light enough to travel long distances and are now found in urban and rural air alike. When inhaled, they may lodge in lung tissue — especially particles smaller than 10 microns — potentially leading to inflammation or respiratory problems.

What are microplastics doing to human health?

This is where the science is still catching up. We know microplastics are in our food, air, and water. We know they’re entering our bodies. What we don’t fully know yet is what they’re doing once they get there.

In 2022, Dutch scientists discovered microplastics in human blood for the first time, prompting concerns about their ability to circulate systemically, per data published in Environment International. PET, polyethylene, and polystyrene — common in packaging — were all detected. The particles were small enough to potentially travel to organs and cross biological membranes.

One concern is that microplastics may trigger immune responses. Particles that lodge in tissues could cause chronic inflammation, just as asbestos fibres do. Others may pass into the bloodstream, cross the blood-brain barrier, or accumulate in the placenta — all possibilities raised in recent animal studies.

Another key issue is endocrine disruption. Plastics often contain additives like phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA), both of which are known to interfere with hormone systems. These chemicals have been linked to reproductive problems, metabolic disorders, and even certain cancers. Microplastics may act as carriers for these substances, delivering them directly into the human body.

There’s also concern about the long-term, cumulative exposure. While a single microplastic particle might not cause harm, the accumulation over time — especially in vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women, and those with pre-existing health conditions — could have significant implications.

What’s being done about it?

While the problem is daunting, efforts are underway to address it. Several governments, industries, and NGOs are developing strategies to reduce the production and spread of microplastics.

Regulatory action: The UK banned microbeads in rinse-off personal care products in 2018. The EU is working to restrict intentionally added microplastics in cosmetics, detergents, paints, and more. Countries like France are introducing requirements for microfibre filters on all new washing machines by 2025.

Corporate accountability: Some companies are pledging to reduce plastic use, redesign packaging, and develop bio-based alternatives. Adidas, for instance, has committed to using only recycled polyester in its products by 2024.

Scientific innovation: New technologies are emerging to capture microplastics before they reach ecosystems — such as washing machine filters, wastewater treatment upgrades, and even ocean-cleaning devices that target floating plastic.

Consumer awareness: Campaigns like Plastic Free July and organisations such as Surfers Against Sewage and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation are raising awareness and pushing for circular economy models where materials are reused, not discarded.

Research funding: Programmes like the EU’s Horizon Europe and the UKRI Plastic Research and Innovation Fund are investing in research into the health and environmental effects of microplastics, alongside technological solutions.

What can we do?

Systemic change will take time, but individuals can help drive momentum by making conscious choices:

Opt for natural fibres: Clothes made from cotton, wool, and hemp shed fewer harmful fibres than synthetics.

Use washing machine filters: Microfibre-catching devices like Guppyfriend bags or built-in filters can significantly reduce plastic shedding.

Avoid plastic-heavy products: Choose packaging-free or plastic-free options when shopping, especially in food and personal care.

Say no to single-use: Reuse wherever possible — bottles, bags, containers — and buy durable items that last.

Support responsible brands: Look for companies actively working to reduce their plastic footprint.

Push for policy: Advocate for stronger legislation around plastic waste and microplastic emissions.

Microplastics are one of the clearest examples of how convenience culture can come with hidden costs.

They’re small, but their reach is global. They travel through air and water, work their way into animals and humans, and stay in the environment long after their original purpose is forgotten.

As we learn more about the consequences of microplastic exposure — from the soil beneath our feet to the bloodstream in our veins — the urgency of action becomes harder to ignore. Reducing plastic pollution is no longer just an environmental issue. It’s a health issue. An agricultural issue. A human rights issue. And it will take all of us — from lawmakers and manufacturers to consumers and citizens — to turn the tide.

Because if we don’t act, we risk creating a world where plastic isn’t just everywhere — it’s in everything.