The last few centuries have seen some devastating losses in the natural world.

Species that once shaped ecosystems and dazzled early naturalists are now reduced to bones in drawers or blurry black-and-white photographs. While overhunting, habitat destruction, pollution, and invasive species all played their part, what stings the most is knowing that many of these extinctions might have been preventable with the technology and knowledge we have today.

From AI-powered wildlife monitoring to real-time GPS tracking, precision habitat mapping, reproductive science, and sophisticated anti-poaching tools, today’s conservation arsenal is vast. Unfortunately, for many species, these advances arrived just a few decades too late. However, by looking back, we can better understand what we must protect going forward.

Here are some recently extinct animals that might still be part of our world if today’s technology had been available in time.

1. Passenger pigeon

At one point, passenger pigeons were so numerous in North America that flocks would darken the sky for hours. But in less than 100 years, relentless commercial hunting and deforestation drove them to extinction. With today’s data modelling and satellite tracking, we could have seen their catastrophic population crash coming long before it was irreversible. High-resolution imaging, acoustic monitoring, and habitat corridor planning might have preserved breeding grounds. And with early intervention, a captive breeding programme combined with modern genetic analysis could have kept the species viable.

2. Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)

This striped marsupial predator was wiped out due to bounty hunting, habitat destruction, and a lack of ecological understanding. Declared extinct in the 1930s, the thylacine’s decline might have been halted with camera trap networks, community outreach, and legal protection backed by scientific evidence. Today’s wildlife genetics tools could have mapped remaining populations and guided captive breeding. Modern interest in de-extinction often circles back to the thylacine—a poignant reminder of what we lost and why timing matters.

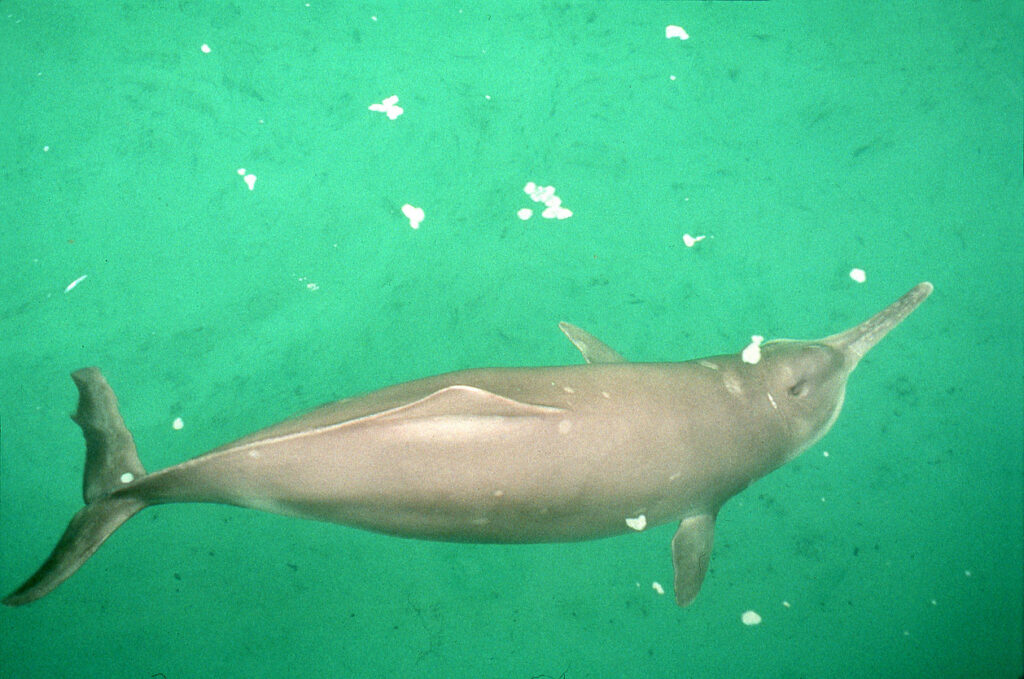

3. Baiji river dolphin

This gentle freshwater dolphin was once a common sight in China’s Yangtze River. Pollution, boat traffic, and unregulated fishing decimated their numbers until they were declared functionally extinct in the early 2000s. Current aquatic conservation tech—like sonar-free fishing gear, real-time pollution tracking, underwater acoustic monitoring, and shipping lane restrictions—might have allowed them to recover. Conservationists could have used AI-powered modelling to predict danger zones, while awareness campaigns amplified through social media might have generated enough pressure for policy change.

4. Pyrenean ibex

Also known as the bucardo, this mountain goat went extinct in 2000 due to hunting pressure and habitat degradation. Its environment was rugged and difficult to access, which limited conservation efforts. Today’s habitat mapping tools, thermal drone surveillance, and remote monitoring could have helped maintain a stable population. In 2003, scientists cloned one from frozen tissue—a short-lived success, but a clear demonstration of how genetics has evolved. With more time and research, we might have had a sustainable plan before it was too late.

5. Caribbean monk seal

Hunted for its blubber and forced out by human encroachment, this seal disappeared from Caribbean waters by the mid-20th century. Had satellite tracking, underwater camera systems, and marine protected zones existed then, the story might have ended differently. Anti-poaching enforcement via drone patrols and marine corridor mapping could have secured habitat. Education campaigns, now common in marine conservation, could have changed public perception in time to save them.

6. Pinta Island tortoise

Lonesome George became a global symbol for species on the edge. He was the last known member of his Galápagos subspecies until his death in 2012. Earlier use of genomic analysis and reproductive science might have allowed for hybridisation or cloning programmes before genetic bottlenecking became too severe. Invasive species control—especially rodents and goats introduced to islands—could have protected food sources and nesting areas, giving the species room to recover.

7. Western black rhinoceros

Declared extinct in 2011, this rhino subspecies was the victim of intense poaching driven by illegal horn trade. Today, thermal imaging, AI-enabled poaching detection, and ground-to-air ranger coordination using GPS have drastically improved rhino protection elsewhere. Fertility tracking, sperm banks, and embryo implantation are now possible conservation tools. If implemented earlier, they could have bolstered dwindling populations and introduced new individuals into secure, managed areas.

8. Stephens Island wren

One of the few flightless songbirds ever discovered, this tiny bird was wiped out just years after cats were introduced to its island habitat in New Zealand. Today, strict biosecurity protocols, invasive species detection systems, and remote predator traps could have protected its fragile environment. Real-time alerts from smart collars or tagged cats would have raised red flags, and isolated breeding facilities could have safeguarded backup populations.

9. Great auk

A flightless seabird from the North Atlantic, the great auk was easy prey for human hunters. By the mid-1800s, it was gone. With the tools we have now—GPS tagging, maritime traffic control, protected marine reserves, and remote island surveillance—we could have shielded nesting grounds from exploitation. Egg collection could have been restricted, and captive breeding might have stabilised the species while wild populations were given space to rebound.

10. Spix’s macaw (in the wild)

Though captive populations remain, this stunning blue parrot disappeared from its natural Brazilian habitat due to logging and the illegal pet trade. Today, real-time deforestation alerts, biometric tracking, and AI-assisted breeding efforts are fuelling reintroduction attempts. Earlier implementation of trade bans, habitat reforestation, and captive population coordination might have preserved a continuous wild presence.

11. Toolache wallaby

This graceful marsupial from southeastern Australia went extinct in the 20th century due to hunting and land conversion. With today’s drone surveying, habitat modelling, and satellite collars, conservationists could have identified safe zones and preserved critical corridors. Education campaigns and hunting restrictions backed by visual data might have changed public attitudes in time.

12. Dusky seaside sparrow

Native to Florida’s salt marshes, this bird went extinct in the 1980s after its habitat was drained for development. Habitat loss and poor planning were the main culprits. With today’s wetland restoration software, population modelling, and nesting behaviour sensors, the impact could have been reversed. Controlled burns, seasonal flooding patterns, and buffer zones could have kept the species going.

We can’t bring back what we’ve already lost, but we can get better at protecting what’s still here.

The animals on this list serve as reminders of what happens when action comes too late, and when politics or short-term thinking overrides ecological reality. Today’s technology is powerful, but it needs to be paired with urgency, funding, and the will to act. If we do that, maybe the next generation won’t be reading about even more species that slipped through our fingers.